President: Hon. Judge Ema Aitken | Vice-President: Helen Rice

In the July newsletter, AWLA reported its concerns about the treatment of sexual offending by members of the judiciary, noting that in her book, “Without Prejudice – Women in the Law”, Gill Gatfield details:

“… in July 1996, a High Court judge revived concerns about the judiciary’s adherence to rape myths. While summing up in a rape trial at the New Plymouth High Court, Justice Morris told the jury that if every man throughout history had stopped the first time a woman said ‘no’, the world would be a much less exciting place. Within 45 minutes, the jury acquitted the defendant…

AWLA reported to its members:

Perhaps what has incensed people the most, and particularly women and members of the legal profession is that this comment is not an isolated one…” (Gill Gatfield Without Prejudice: Women in the Law (Brooker’s, Wellington, 1996) at 264).

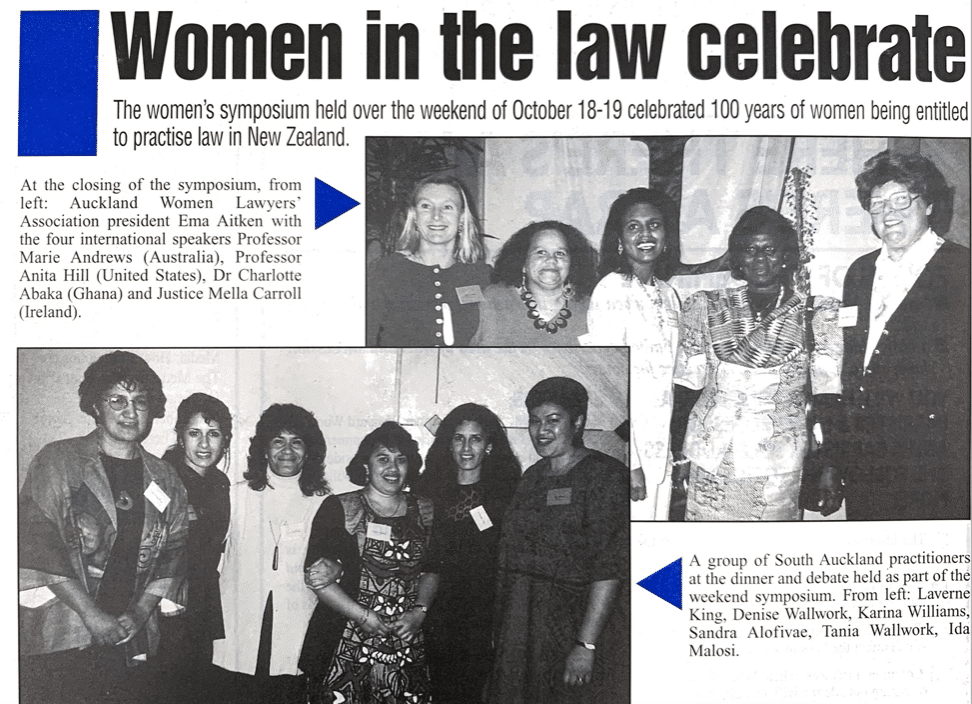

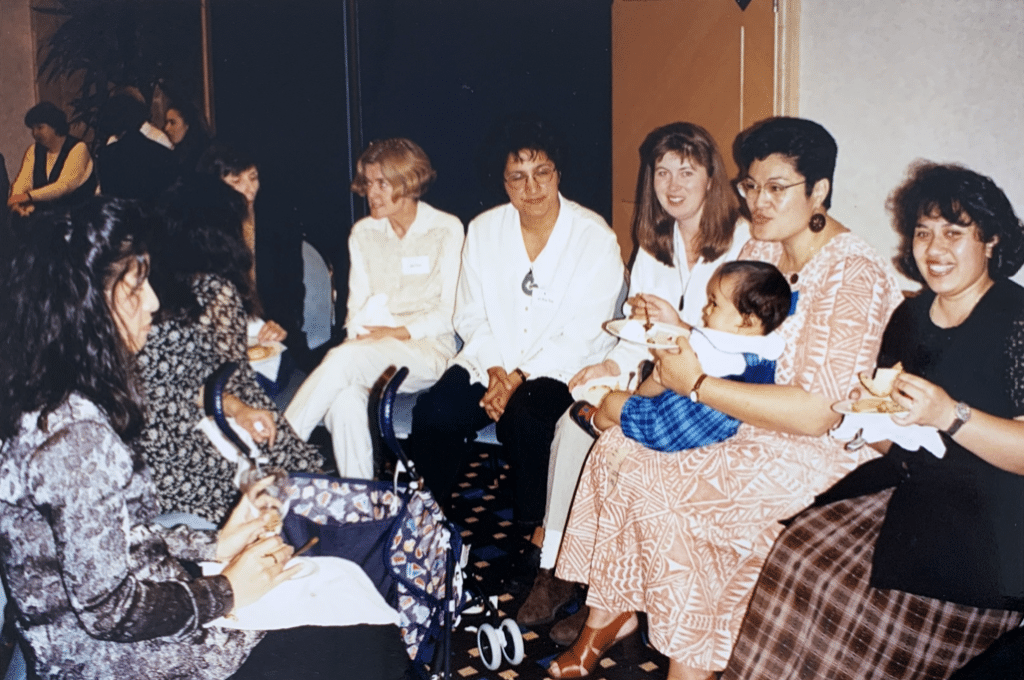

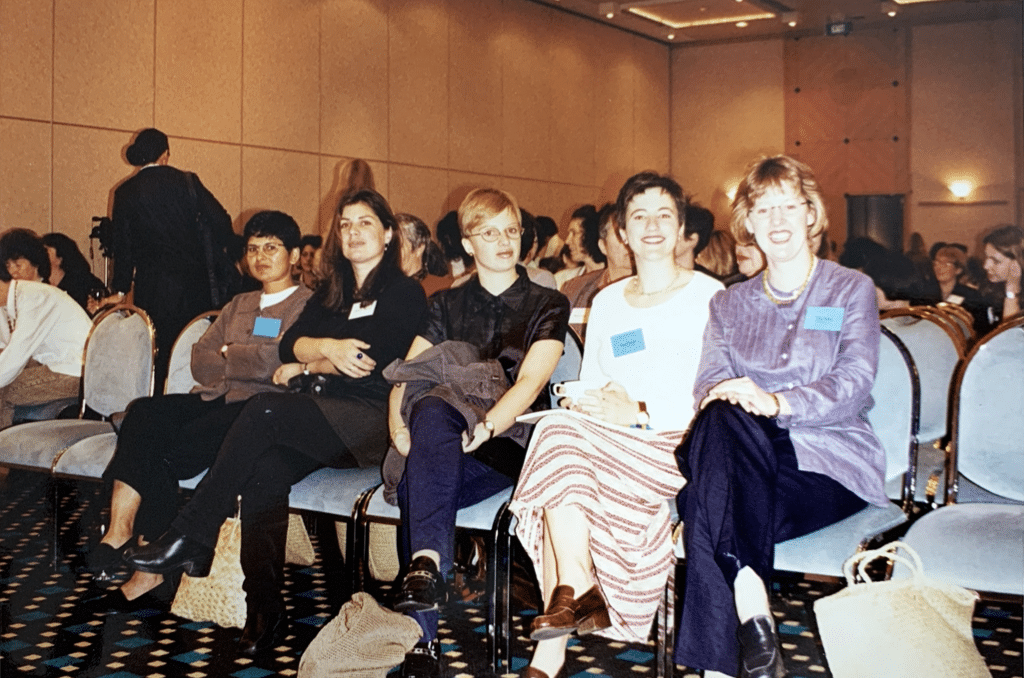

AWLA held a two-day symposium in October to celebrate the 100th year since legislation was passed allowing women to practise law. The prior legislation, the Law Practitioners Act 1882 specified that lawyers could only be men. Other legislation at that time defined women as “suffering” under a “disability”, which was also the meaning applied in common law.

The symposium focused on the legal position of women today, both nationally and internationally:

“Discussion ranged from the thorny issue of sexual harassment to the soon-to-be-enacted Irish divorce law, aboriginal land rights issues and the legality of polygamy and female circumcision in Ghana” (Jenni McManus “Women Lawyers Celebrate” The Independent (New Zealand, 25 October 1996) at 22).

The event was attended by over three hundred women, and had a range of prominent international guest speakers including:

- Professor Anita Hill from the USA, an expert on race and gender issues. Known for raising a sexual harassment complaint against US Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas in 1991, which ignited a conversation and raised awareness of sexual harassment in the American workplace;

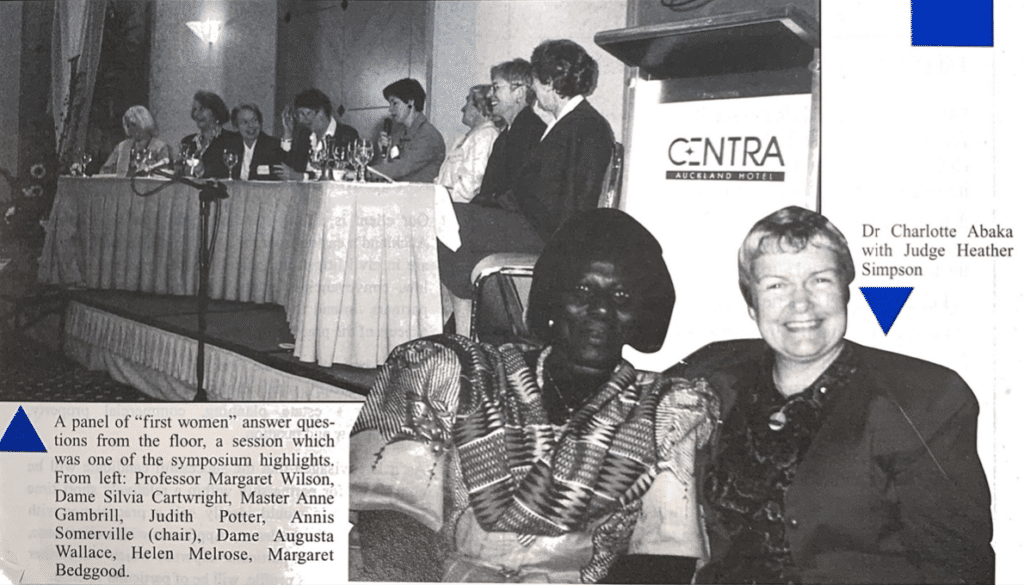

- Dr Charlotte Abaka of Ghana, a medical doctor and dentist who established the National Council of Women in Ghana and was a member of the United Nations’ Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women;

- Justice Mella Carroll from Ireland, a Judge of the High Court in Dublin who had recently successfully chaired the Irish Commission on the Status of Women which recommended a referendum on divorce; and

- Professor Marie Andrews of Australia, who was a specialist in Aboriginal land rights and gender issues.

A “first women” panel was held, with topics of discussion including role models, how they were supported, why they chose law and their advice for the future generations of women lawyers. The panelists were:

- Hon. Dame Sylvia Cartwright ONZ PCNZM DBE QSO DStJ, the first woman High Court judge and first woman appointed as chief judge of the District Court;

- Margaret Wilson DCNZM, the first woman to be appointed as dean of a Aotearoa New Zealand law school and the first woman to become a professor of law;

- Hon. Judith Potter DNZM CBE, the first woman on a district law society council and the first woman to be president of both the NZLS and ADLS;

- Hon. Anne Gambrill CNZM, the first woman appointed to the High Court, as a master;

- Hon. Dame Augusta Wallace DBE, the first woman District Court judge;

- Helen Melrose, the first AWLA president and a founding member of the organisation;

- Margaret Bedggood CNZM QSO, the first woman Human Rights Commissioner; and

- Chaired by Annis Somerville, the President of the Otago District Law Society.

Gill Gatfield’s book “Without Prejudice – Women in the Law” was launched at the symposium. The book provided a comprehensive review of women within the legal profession and argued that substantive progress had not been driven by the profession:

“Law firms and law societies have tended toward a reactive decision making style. Most follow rather than lead in terms of business, management and human resource thinking. Instead the significant changes enabling women to advance within the profession have been achieved through changes in government policies relating to employment and the family, changes in the education system or the business community. Without Prejudice aims to encourage and equip the profession itself to initiate change” (“Women in Law: Centenary Celebration – Without Prejudice: Women in the Law Breaking down the barriers and constructing new paths forward” Law Talk (New Zealand, October 1996) at 14).

In 1996, AWLA made submissions in two prominent cases, Ruka v Department of Social Welfare and Z v Z.

Ruka v Department of Social Welfare [1997] 1 NZLR 154 was an appeal from conviction for what is commonly called social welfare benefit fraud.

AWLA sought and obtained leave to appear as amicus curiae in this appeal on the basis that the case raised issues of considerable public importance, particularly to women. The Court noted in its judgment that it was greatly assisted by the submissions of Denese Bates KC and Frances Joychild KC, who appeared for AWLA.

The appellant beneficiary, Ms Ruka, lived with and was in a de facto relationship with Mr T for about 18 years. During that time, Mr T abused her. Ms Ruka never received any financial support from Mr T, and was left to fend for herself and their child. During the relationship, Ms Ruka supported herself and her child by earning wages when she could and for the rest of the time by social welfare benefits. When applying for welfare benefits, she did not disclose her relationship with Mr T to the Department of Social Welfare.

Ms Ruka was prosecuted in the District Court on seven charges of wilfully omitting to supply material particulars and six charges of fraudulently using a document to obtain a pecuniary advantage. Judge Bouchier found that Ms Ruka was in a de facto relationship with Mr T, and that she had an intent to defraud the Department. In Ms Ruka’s unsuccessful appeal to the High Court, Barker J found that there were some indicia of a relationship in the nature of marriage, and the fact that Ms Ruka suffered from battered woman’s syndrome could not negate fraudulent intent. With leave from the High Court, Ms Ruka appealed to the Court of Appeal.

In the Court of Appeal, it was argued that no fraud was committed because Ms Ruka was at all relevant times suffering from battered woman’s syndrome which meant that she lacked the necessary mental commitment to a relationship so as to be living in a “relationship in the nature of a marriage” for the purpose of s 63 of the Social Security Act 1964. It was argued that she was incapable of rational decision-making and, in particular, unable to take steps to terminate her relationship with Mr T.

In delivering the majority decision, Thomas J held that an assumption of financial interdependence is essential before a relationship can be regarded as being in the nature of a marriage. Physically, aspects of the relationship remain relevant as indicia of a relationship in the nature of a marriage, but they must be taken into account having regard to the effects of the battering relationship or violence. Less weight, if any, would need to be given to, for example, the fact that the parties live together when the woman is staying under the same roof as the perpetrator out of fear and helplessness.

The Court held that there was no doubt that Ms Ruka suffered from battered woman’s syndrome, and that the mental and emotional commitment necessary to comprise a relationship in the nature of marriage did not exist in this case. The Court also held that financial independence or responsibility in this case was totally lacking. Ms Ruka’s convictions were quashed.

AWLA also made submissions in Z v Z [1997] 2 NZLR 258, where it was granted leave to appear as amicus curiae on the issue of future earnings. Denese Bates KC and Hon. Vivienne Ullrich KC appeared for AWLA at the hearing.

This was a Court of Appeal case concerning whether a spouse’s earning capacity is “property” within the meaning of the term in the Matrimonial Property Act 1976. More broadly, the Court was asked to determine whether the increase in earning ability gained during the marriage from acquiring degrees and qualifications and improving career skills and expertise could constitute matrimonial property and therefore, whether one spouse could be compensated after separation for helping create a potential for greater lifetime earnings for the other spouse.

The parties to the litigation had married in 1966 and separated 28 years later. When the parties married, the wife was working and earning a higher salary than her husband, who was studying at the time. The wife stopped working a year before the birth of the couple’s first child. The husband qualified as an accountant in 1968 and became a partner in an accountancy firm. In 1994 (the year of separation), he earned over $300,000 per year.

The Court held that it was not Parliament’s intention to include a spouse’s enhanced earning capacity within the scope of matrimonial property for the purposes of the Act. The Court acknowledged it had reached that conclusion notwithstanding the strength of the argument advanced for the wife that to treat enhanced earning capacity as matrimonial property was consistent with the policy and spirit of the legislation. The long title of the Act supported the wife’s argument. Having regard to this premise, it was difficult to refute the contention that excluding a wife whose contribution to the matrimonial partnership has been the management of the home and the care of the children from sharing in the husband’s increased earning power, which they had jointly worked for, perpetuated the injustice the Act was aimed at remedying. However, as the Court was bound to interpret the Act, not to amend it, it had to give effect to Parliament’s intention and find that a spouse’s enhanced earning capacity did not constitute “property”.